Stop Trying to Be Good — Be Black

By Jamilah Lemieux

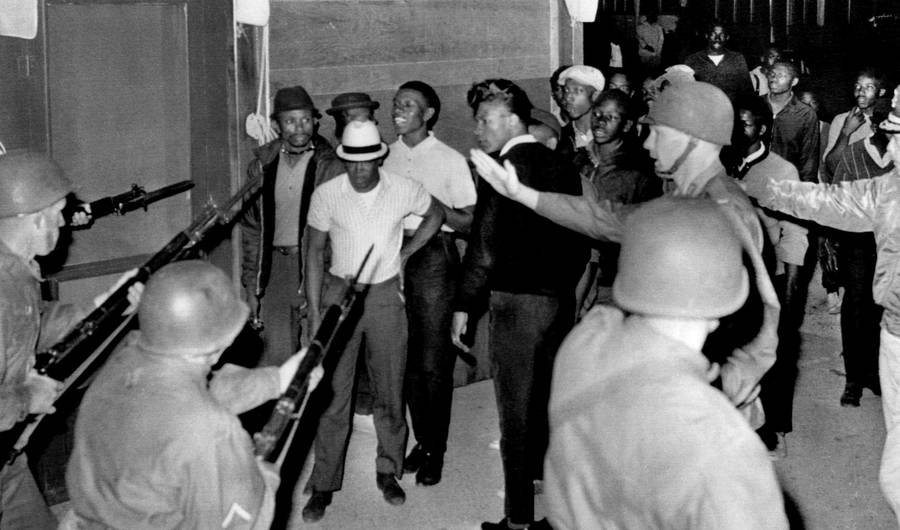

Some of the most iconic images of nonviolent protest from the 1960s show well-groomed black folks being beaten, bitten by dogs and dragged by police officers. I marvel at the fashion worn by these meticulously coiffed protesters, who knew they would return home — if they returned home — with blood on their nylons and busted loafers. Wouldn’t sneakers and jeans have been more comfortable, or less expensive to replace?

Nevertheless, I understand the sartorial choices of our forefathers and foremothers who occupied public spaces that had been privatized by Jim Crow. I understand why dressing sharp mattered to them. It wasn’t about merely looking good; it was about being perceived as good. Good enough to be treated with dignity. Good enough to enjoy basic human rights and freedoms. Good enough to be American. Good enough to live.

Alas, the face of protest and organized resistance has changed quite a bit in 50 years. The appearance of the most visible and consistent black youth activists today is as different from their elders as their messaging. Phillip Agnew of the Dream Defenders is very much in the rhetorical tradition of Martin Luther King, but his neck tattoos and political T-shirts differentiate him from the slain civil rights icon nearly as much as his intersectional, feminist, pro-LGBT approach to freedom-fighting.

It seems that for folks like Agnew, one of the great lessons of the 1960s is that we cannot make white people love us by being “good” and mannerable in our resistance to oppression. Being college-trained and well-spoken, employed and law-abiding may — may — take you to the middle-class dream so many of us pine for. But what it will not do is protect you from the crushing white supremacy that is America’s greatest national accomplishment.

We cannot make white people love us by being “good” and mannerable in our resistance to oppression.

Though many of us seem to know this, we are consistently presented with messaging that would suggest otherwise. President Obama, for example, has made mention of the need for African-Americans to behave “well” or “appropriately” in the wake of the killings of Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown and Eric Garner. His imaginary cousin “Pookie” has become a symbol for the sort of black person who just can’t get it together. But who has it more “together” than Henry Louis Gates — accosted by a police officer and accused of trespassing in his own home, despite being a distinguished gentleman and senior scholar who walks with a cane?

Don Lemon, the CNN host turned Black Twitter punching bag (and rightfully so), famously supported Bill O’Reilly’s anti-black rhetoric in 2013. Lemon claimed shortly after the George Zimmerman verdict that black people should stop using the word “nigger,” stop sagging, stop littering, start finishing formal education and have children only when married if we wanted a better life in this country. In this rant, and his subsequent defenses of it, he said little of the role that the prison industrial complex, crumbling public school systems and other pillars of structural racism have played in the plight of our communities. Lemon took more umbrage with low-slung jeans than he did with police departments that have abysmal track records of police-on-black violence.

You can hear how widespread these notions of respectability politics are every time the family of a victim of a police killing takes to TV to plead for peace and calm, some going so far as to humanize the killers of their loved ones. In fact, before Mike Brown’s stepfather cried “Burn this bitch down!” the night the grand jury announced its decision not to indict the white officer who killed his son, his name was attached to a public statement that said, “Acting like an animal will not solve the problems of [our] people.”

I have made it my business not to charge black people with the task of humanizing ourselves in the eyes of whites. It doesn’t work. It implies that white approval is something we should aspire to have. It implies that white humanity and worth are somehow superior to ours. It is not our job to end racism, for we did not create it, nor can we be accused of sustaining it.

However, I fully believe it is our charge to dismantle the anti-black attitudes that so many of us carry, in the service of our individual and collective liberation, and to check our respectability politics at any door in which we may enter.

We cannot demand justice for Mike Brown when some of our own people are wringing their hands over the slain teen’s decision to smoke weed.

We can’t use Eric Garner’s criminal record and sale of loose cigarettes as a reason to limit our support of his family to a quiet Facebook “like” on an “I can’t breathe” meme.

We should encourage members of black Greek-lettered organizations to wear paraphernalia while protesting, as opposed to demanding that members do just the opposite.

It’s impossible to claim we want greater respect for black womanhood when we too will shame a woman for having numerous out-of-wedlock births, to the point it seems we’d sooner excommunicate her from the community than figure out ways to support her family’s well-being.

When students at Howard University (my alma mater) replaced the school’s flag with the Pan-African one, they should have been supported by administration, not publicly chided.

A natural hair movement that is centered around loose curls, long waves and other hair textures that have long been deemed “acceptable” is not one rooted in pro-blackness.

Justice and freedom will remain evasive so long as we treat poor, uneducated and disenfranchised brothers and sisters with the same contempt that we face from our oppressors. So long as the standard by which we judge our brothers and sisters, ourselves, is one we didn’t create, we will be crushed by the weight of our inability to live up to it.

This essay is part of the “Shifting Perceptions: Being Black in America” series commissioned by Perception Institute in partnership with Mic.

This essay is part of the “Shifting Perceptions: Being Black in America” series commissioned by Perception Institute in partnership with Mic.

Jamilah Lemieux is a senior editor for Ebony.