The Life and Breath of Black Men

By Mark Anthony Neal

The most timeless trope of black men and boys is that aligned with their perception in the white imagination: black men who possess a level of strength, rage and pure energy that is beyond human. One need only look at the character of Gus in the 1915 film Birth of a Nation to find an image that has been continuously remixed and circulated in American culture as a stock representation of black masculinity: Gus, played by white actor Walter Long in blackface, follows Flora, a white woman, into the woods. Fearing rape by a “black man,” Flora kills herself by jumping from a cliff.

Similarly, Darren Wilson described Mike Brown as a “demon” and “Hulk Hogan”-like. Perceptions like these fuel the fear of unarmed black males, as well as the fascination with elite black male athletes.

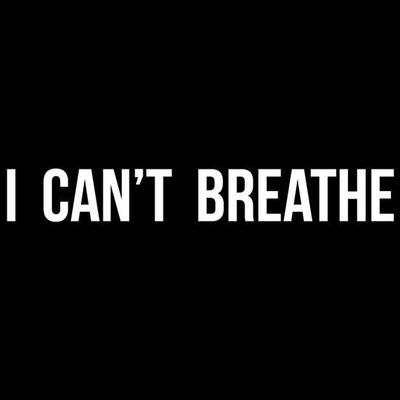

Yet, as evidenced in the cries from the late Eric Garner, “I can’t breathe,” such mythology obscures the fragility of black life. Black men and women’s vulnerabilities remain largely unseen to the public, except as statistical data reminding us about racial health care disparities. Ironically, these health disparities suggest a crisis as threatening, if not more so, than aggressive policing. Even as we demand an end to state-sanctioned violence against blacks, we must simultaneously recognize that preventable diseases like heart disease, hypertension and diabetes are as deadly as any police officer’s chokehold.

On the day a Staten Island grand jury decided not to indict police Officer Daniel Pantaleo for Garner’s death, Rep. Peter King (R-N.Y.) forecasted that Garner eventually would have fallen victim to heart disease caused by his obesity — even if the NYPD’s inept training had not befallen him.

“You had a 350-pound person who was resisting arrest,” King told CNN, referring to the black man whose choking death by police was captured on video. “If he had not had asthma and a heart condition and was so obese, almost definitely he would not have died from this.”

Rep. King’s comments, however insensitive and blatant in their attempt to displace clear police malfeasance, should give us another reason to pause. Mr. Garner, and so many men like him, have long struggled to breathe.

Mr. Garner was selling “loosies” on a corner, an indication that he was tethered to the informal economy. This “job” was surely something for which no one should have been choked to death. Given historical instances when black men have been denied consistent access to traditional labor opportunities, even working-class and poor black men with full-time jobs are often forced to get creative in order to achieve a livable wage. Further, as we witness fast-food workers struggle with global corporations over better wages and adequate health care, it goes without saying that selling loosies likely doesn’t include a health care package.

And despite glamorous depictions of hustling found in popular culture — often via a generation of now-millionaire rappers, who make deals using their surnames — hustling is a rather mundane activity, filled with high levels of stress. The term “hustling” serves as a metaphor for both unlawful activities and the haphazardness of everyday life for those involved. Many of these men and their families live in precarious environments that lack healthy food options adding to their health challenges.

The sad reality for these men, like many hourly wage workers, is that the time spent at a doctor’s office means lost wages. This confluence of environmental factors conspires with aggressive policing and racist infrastructures within education, the judicial system and housing to deny black men the ability to breathe freely — and thus live freely.

“I can’t breathe.” This is me on Mother’s Day 2008, gasping for air as my wife’s stricken face suggested that some tragic, life-altering event was about to occur.

How I got to that point was not some mystery: hypertension brought on by lack of exercise and too many processed foods, a high-stress lifestyle and sleep deprivation caused by sleep apnea that was not in check, despite my use of the CPAP machine. Finally, there was the unwillingness to take the time to see a physician on a regular basis. However, my body had other ideas. Its final warning came in the form of a deliberate plan to deny me the ability to breathe. No under-trained, fearful or racist police officer was needed.

Virtually every health index that compares the lives of black men to their white peers finds black men have disproportionately higher rates of obesity and hypertension or high blood pressure, all of which directly correlate to high rates of heart disease. Sleep apnea is an obstructive sleep disorder characterized by heavy snoring and numerous breathing stoppages described as “events.” According to a recent study from Wayne State University researcher Dr. James A. Rowley, black men also suffer from sleep apnea at much higher rates than other demographic groups.

Whether or not I should have known better is not the point; black men have been socialized to ignore the aches and pains that accompany the breakdown of our bodies. Indeed, if we are black men of heft, there’s a mythology that suggests we should just “man up” — that is, until we can’t actually breathe. This is a point made by Vanderbilt University researcher Derek M. Griffith, who in a 2012 study published in the American Journal of Public Health which noted that notions of good health among black men are largely connected to questions about their ability to adequately fulfill “social roles such as holding a job, providing for their family, protecting and teaching their children.”

Mr. Garner’s last words — “I can’t breathe” — have become a meme that has inspired many around the globe to protest aggressive policing. Yet even if the police reforms needed to spare Mr. Garner’s life had already been established at the time of his death, I wonder if he still would have succumbed to the kinds of avoidable maladies brought on by health care inequities. Like that police officer’s chokehold, those preventable diseases might have left him gasping, “I can’t breathe.”

This essay is part of the “Shifting Perceptions: Being Black in America” series commissioned by Perception Institute in partnership with Mic.

Mark Anthony Neal is a Professor of African & African American Studies and the founding director of the Center for Arts, Digital Culture and Entrepreneurship (CADCE) at Duke University. He is the author of several books including the recent ‘Looking for Leroy: Illegible black Masculinities’ (NYU Press). The 10th Anniversary Edition of Neal’s ‘New Black Man’ was published this year.