Every patient should be able to trust that they will receive excellent health care and that providers will treat them with respect and dignity.

Health care providers are vulnerable to biases that can affect diagnosis and treatment decisions. Research has identified interventions that can interrupt those biases. Patients’ lives and well-being are at stake.

We know that work needs to be done to ensure access to care for all communities – which is critical work at the structural level. What is also necessary is to address how patient race and ethnicity affect the quality of care patients receive. The outcome differences are particularly acute for Black and Indigenous patients – with the impacts on Black patients clearly tied to interactions with health care providers.

Since the 1990s, researchers have examined how unconscious mental processes may be contributing to the serious differences in healthcare outcomes between Black and White patients. These disparities are real and quite serious. Black people fare worse in healthcare outcomes in virtually every category, including chronic diseases, cancer, heart disease, diabetes, stroke, and life expectancy overall. Furthermore, studies show that racial and ethnic discrimination are associated with adverse health outcomes, including elevated blood pressure, higher instances of substance abuse, and obesity.

Studies of implicit bias among physicians reveal that physicians hold the same biases, at the same rates, as the general public, tending to favor white people over black people and Latinos. Tests also show that doctors tend to hold stereotypes of black patients as uncooperative, which can lead to differences in the kind of care they prescribe.

Racial anxiety also helps shape healthcare outcomes. Even if a doctor prescribes the same treatment to Black and White patients, if racial difference shapes their interactions with patients, it can impact health outcomes. Research shows that physicians working with patients of color tend to be less empathic, move faster through their visits, and are less likely to engage patients in medical decision-making. In addition, black patients experience greater levels of distrust towards white providers in clinical settings, and black patients who have a white doctor have been shown to be less likely to schedule appointments and more likely to delay or postpone appointments. The creation of remedies that address implicit bias, racial anxiety and stereotype threat in health care is urgently needed.

Racial disparities in health treatment are well-documented and widespread… Black patients received a poorer quality of care in studies involving cancer treatment, cardiovascular diseases, kidney transplants, children’s medication, pain management, and many other areas.

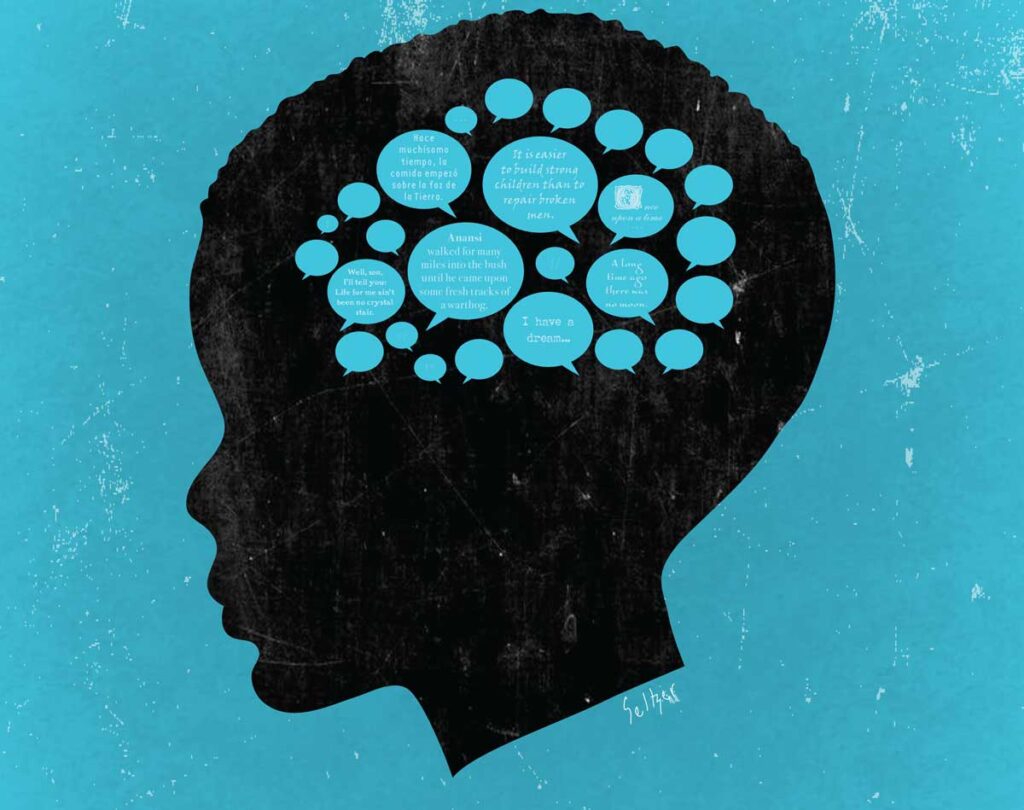

Various Factors contributing to discrimination in health care & How Narrative can positively impact outcomes